Krakow, 17. sept. 2025: Under konferansen til International oral History Association (IOHA.org) 16-19.september 2025, vart hovudinnlegget frå Memoar framført at Bjørn Enes. Det skjedde under delseminbaret «Ethics and metholdogy» onsdag 17/9. Teksten til innlegget fylgjer under bildet.

My points are:

- Oral history and storytelling are different disciplines, but not strange to one another

- Both belong to the intangible cultural heritage.

- Oral historians should use all available tools to bring ordinary people’s life stories into the public discourse.

- Re-telling oral history interviews is one such tool.

My first experience with this was so beautiful, I will never forget it. It was part of an experiment during a storytelling festival in a village in western Norway. I should make an oral history interview with Kjellaug Hatløy Bjergene, a – locally – well known and highly respected teacher. Everybody in the village carried memories of her. The experiment was that a professional storyteller, together with a dramaturg, should get the recording of the interview and then create a monologue about Kjellaug – and perform it two days later.

But then the storyteller sent her regrets. She was sick. The festival director said: “Bjørn – you have to do both: Collect her stories – and tell them to the audience. “

I had no idea about how to do it. And I had no time to seek advice – I got this message just minutes before Kjellaug arrived to be interviewed.

But from the moment we sat face to face, I forgot my worries. I was struck by her beauty and wisdom and poetic way of expressing her life story. She was born in 1942, on a small farm in a small village by a small river with a side fjord.

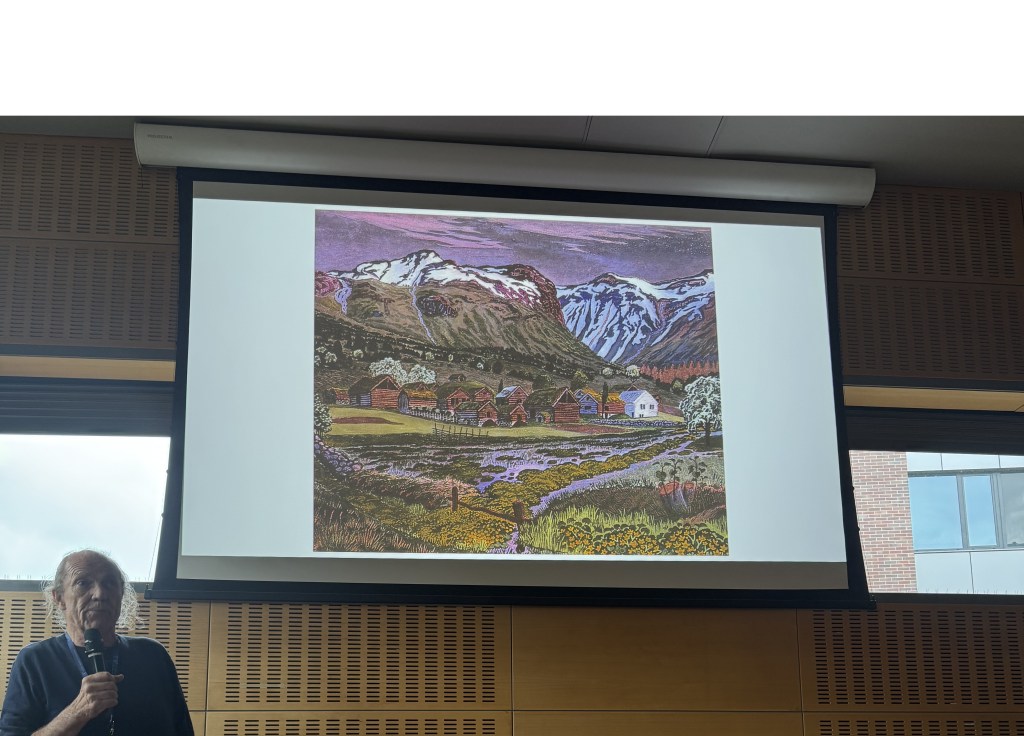

In her family’s living room, there was a painting, brought there by her mother, from her home village by a mountain lake, a day’s travel away.

“Mother told how the painter- Nikolai Astrup – was despised by his father and the villagers, for never getting a proper education and hardly managing to feed his family. Even after he was declared an important contributor to Norwegian art history”.

She told about freedom in her childhood’s world: Climbing mountains, balancing over the river and along steep seashores. And evenings, in front of the painting.

At 14, her father said he did not have the heart to find a job for her. He would let her continue on to a lower secondary school. But there was no such thing in their village. She had to go far, to live in a bedsit.

At 17, after finishing lower secondary, a relative from a mountain village came to her and said: “Please – now, you are educated – come to our village and be our teacher. If not, our children will have to walk the mountains all through winter to school in the next valley”

That’s how she became a teacher. After the war, there was a terrible lack of teachers. So the government started summer courses for unskilled like herself. She attended. After several years she got her papers. A proper education. She got a proper job, in the village where the storytelling festival should take place many years later.

From her position, she had seen every child in the village grow into adults, going away and coming back. There could be no better first hand source to local and cultural history than her. She told me through the 1950ies and 60ies and 70ties – Her radius expanded – she told stories about Norwegian and European and global phenomena, but always with viewpoint from her old village. She married her best friend, and together they did remarkable things.

One day she retired. And then she became a widow. And then she started painting.

“I never did it after 13”, she said. “Drawing and painting was for children. After confirmation, one should do useful things. So – I did useful things all those years. But now – i paint.”

There should be a regional exposition in a gallery in the nearest town. Friends called upon her to present some of her works for the jury. Close to the deadline she did – and three paintings were approved.

I interviewed her for several hours. I wish I could retell more of her story to you. But that is not the topic: The rest of my story here today is about ME.

The interview was ended on Friday afternoon. On Sunday, I should stand in front of an audience who expected a storytelling performance about a person they all had known since childhood. Guess if I was nervous!

Luckily, I had the recordings of the interview. I logged it, that is I wrote down the timecodes for each point where she started a new story. I tried to establish a chronology for her life story.

But then I discovered that actually I was doing something quite different. I could not concentrate on the logging, because my own story disturbed me.

When she told about her childhood freedom, pictures from mine arose inside me. When she told about the painting, I suddenly remembered stories that my mother told, that may have been very much more important to her than I ever understood, about being a girl in the interwar period, a young woman during thee war and a mother in the narrowminded 1950ies.

I thought: But – of course – this is what always happens, when we listen to a fellow human being’s story. It wakes up pictures from our own stories. That may be the main reason why listening is such a difficult skill to learn.

But that is also why sharing of life stories and experiences are such an important part of our intangible culture:

It is sharing, and mixing, and remixing again,

that alters a story

from individual memoir to cultural heritage.

This was what I would do! I would not try to copy a storyteller, jumping around, waving his arms to illustrate trolls or spirits or dragons or damsels in distress.

I would tell, honestly, about how Kjellaug’s story mixed with mine. And thus, may be, I would inspire remixing again in the heads of at least some in the audience.

With that in mind, I threw away my paper, and started over again, this time with three columns instead of two:

- First – the timecodes for each of her new stories.

- Second – the chronology of her life story.

- Third – thoughts and memories that arose from my story.

But I soon found that this was impossible. There was such a chaos of memories and reflexions and feelings and wonderings! Even if I wrote it in key words only, I would not have enough paper. Not to speak about how useless that paper would be.

Then I saw the light for the second time that wonderful day. I remembered a stage director once saying:

“On stage, we perform the art of the moment”

I threw away the paper, and started walking – along roads where I hoped to meet nobody. I discussed it loudly with myself. Now and then i said: “Ah! Remember this on Sunday!”

Sunday came. The stage was in an old barn. It was packed. I had asked Kjellaug to come, to sit beside me. I had decided not to address the audience. I would retell Kjellaugs story to her, in my words, in front of the audience. As a security, I had 8 keywords in my back pocket. But – more important – I had an imagined table between us, with a heap of pictures, ready to be picked in a random order. I was only sure about the first picture; The living room, with the painting and her mother and herself, age about 10, with her drawing pencil.

I saId: “After our conversation, I understand a lot more about the history of Norway and Europe and the world in our era”.

I picked pictures from the imagined heap, triggered by comments or body expressions from her or hearable responses from the audience. I forgot the keywords, but I never needed to pick them up, because she was listening so intensely to me. No one in the audience rose and left. The last thing I told her, was about a compliment I had heard about her picture in the exposition. And I asked: If you did not have to do all those useful things – would you perhaps have been in the National Gallery, beside Nikola Astrup?

You could have heard a needle fall in the barn.

“I will never know”, she said.

*

So – again: My points are:

- Oral history and storytelling are different disciplines, but not strange to one another

- Both belong to the intangible cultural heritage

- Oral historians should use all available tools to bring ordinary people’s life stories into the public discourse

- Re-telling oral history interviews is one such tool.